|

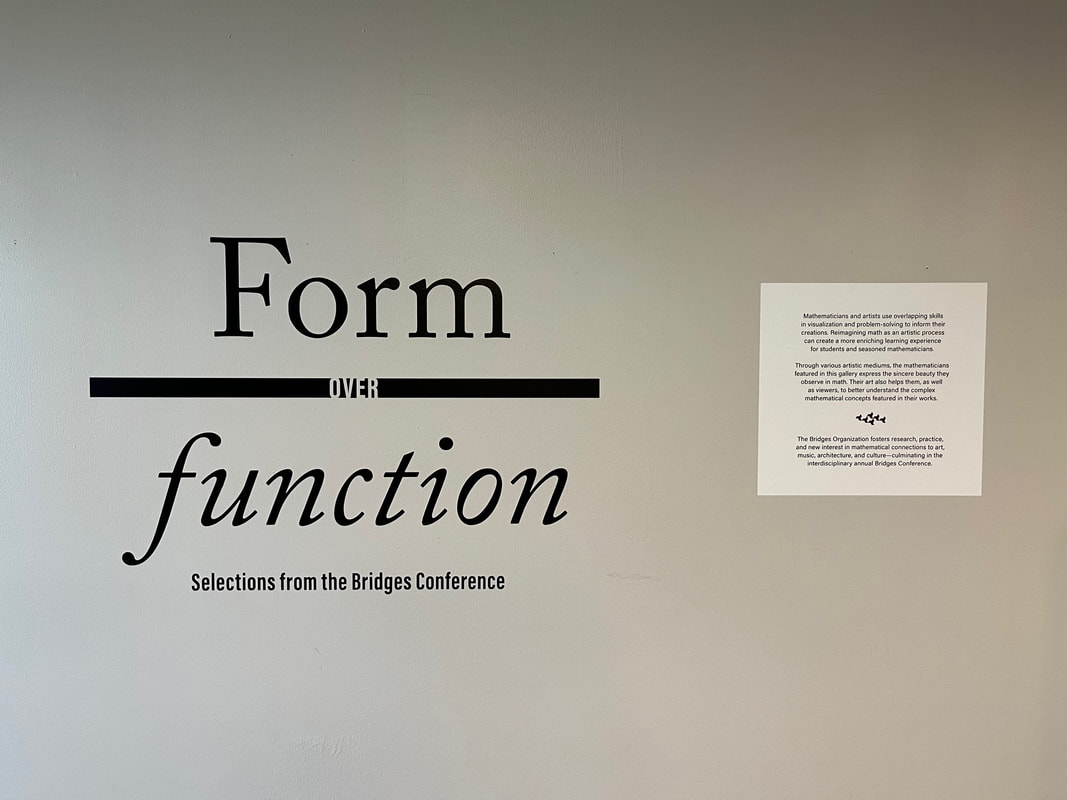

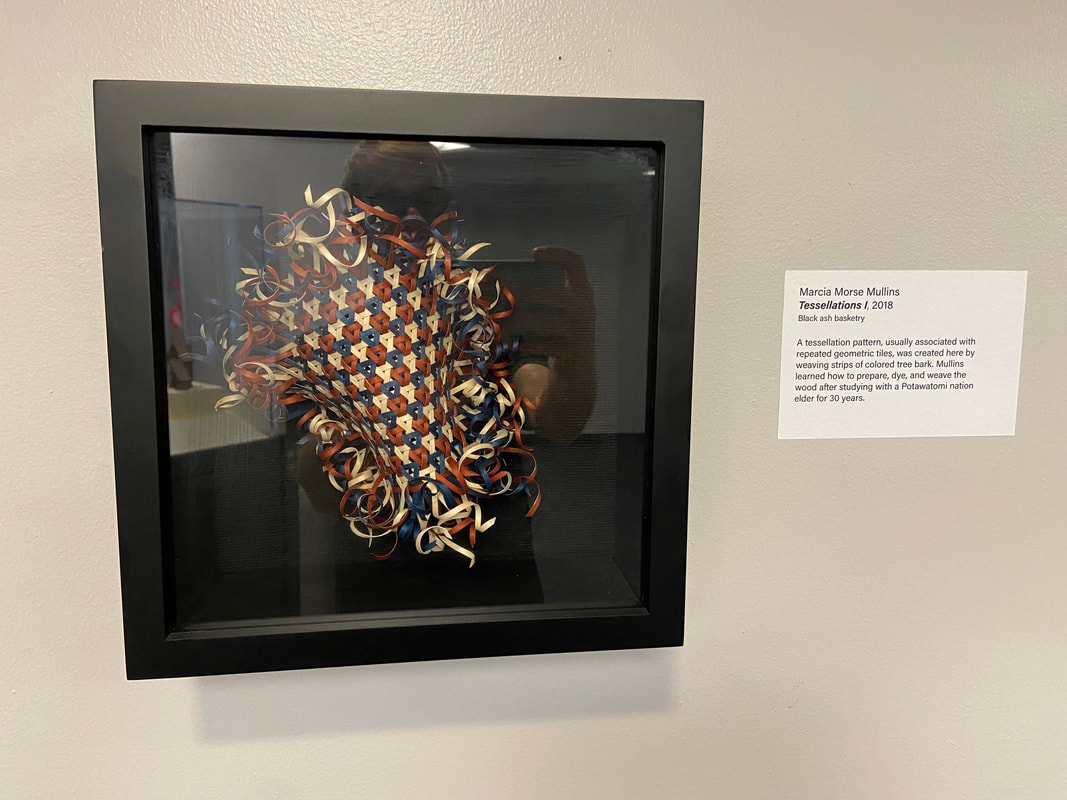

The Science Museum of Virginia is celebrating mathematical art with an exhibit of 15 pieces from previous Bridges Art Exhibitions titled Form over Function. This exhibit opened April 10, 2024 and will be displayed for one year. Included is Marcia's weaving called "Tessellations I", which graced the cover of the Joint Mathematics (now Bridges) Convention catalogue in 2019.

Mathematicians and artists use overlapping skills in visualization and problem-solving to inform their creations Reimagining math as an artistic process can create a more enriching learning experience for students and seasoned mathematicians. Through various artistic mediums, the mathematicians featured in this gallery express the sincere beauty they observe in math. Their art also helps them, as well as viewers, to better understand the complex mathematical concepts featured in their works. I am often asked whether one can make baskets with invasive plants, and the short answer is 'yes'. The full answer has many considerations, which is the topic of this blog post. Our planet has a large variety of diverse ecosystems. We know where to find a barrier reef, an alpine meadow, or a seaside beach, and we anticipate seeing certain living organisms in each biome. The origin and nature of a species within an ecosystem is distinguished by the terms native, alien, and invasive.

A species can be native, alien, and invasive, according to how its populations exist within various ecosystems. For example, the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) was introduced to New York and Oregon in 1890 for the purpose of insect control. Its population now causes extensive agricultural damage and contributes to the decline of native birds through competition for food and nesting sites. Accordingly, the European Starling is native to Europe and Asia and both alien and invasive in Canada, Central America, and the United States. The response to invasive plants has long been one of eradication, whereby we remove the 'bad' invasive plants in favor of 'good' native ones. This blog will not delve into the ethics of managing invasive species, as each country has its own approach. Suffice to say that here in the United States, spray herbicides are used so many of my recommendations are based in that reality. While land managers and restoration experts focus on eradication programs, basketmakers can make good use of many invasive plants. I once helped a group of weavers remove an entire hillside of Japanese honeysuckle in one week. We did our weaving onsite to avoid introducing honeysuckle to another location, and we each took several lovely baskets home with us. After the honeysuckle spread across the hillside again, we went back for another weaving party. It's important to note that we didn't just park our cars and start collecting. Several considerations come into play when collecting natural materials:

Information specific to utilizing invasive plants for basketry is available at the end of this blog post. The list is organized in alphabetical order by scientific name with the common name in parenthesis. Specific details include a description, the countries in which it is established as an invasive species (as of 2020), and how the plant can be utilized by the basketmaker. Additional collecting notes are provided for some species. This listing is not exhaustive; rather, it is provided as a starting point. Country listings are according to the Global Invasive Species Database (www.iucngisd.org) and do not drill down into states/provinces/local areas. Most of the plants on this list have non-invasive 'cousins' that are also useful for basketry. For example, Clematis reticulata (Netleaf virgin's bower) is native to Florida but Clematis terniflora (Japanese clematis) is an alien invasive. Both can be used for basketry. Finally, this list does not include species that may be aggressive in growth but lack the environmental, economic, or health implications required for classification as an invasive species. A local example of this is Vitis rotundifolia (Muscadine grape), a vigorous, high-climbing vine that happily drapes itself over trees and shrubs. While the species is rather aggressive, it is native to Florida and thus cannot be classified as a Florida invasive. As a basketmaker, I do my part to keep the species under control in my little corner of the world.

"Listen to the Tree." Mike Sagataw, the Potawatomi tradition-bearer who taught me how to select, fell, and transform a black ash tree into weaving splint, had repeated those words as a mantra. "Listen to the tree, for it will speak to you. It will tell you what it wants to become."

Even now, 30 years later, I sometimes find myself complaining into the wind. "These growth rings are fibrous and heavy, but I want to make something light and airy." The wind returns no sympathy, just Mike's voice. "Listen to the tree." I prepare wider, heavier splint and begin laying up a pack basket. The splint does not argue when you pay attention. Last spring, I spent several months on a sculptural form with overlapping layers of weaving. As I worked, the piece sang happily. It took on a fish shape that began morphing into a stylized boat/pod. I added an outer layer of willow to accentuate the boat shape, and as I worked the piece went silent. I removed the outer layer and kicked it to the corner. The fish shape was happy again, and that is all that mattered. Several weeks after finishing Pesca Pod, I heard something calling me. It was the outer layer, wanting its own identity. It sang its own song as I wove, and my first piece of folk art emerged: Gator Bait. Its curious open margin is the result of removing Pesca Pod from its "belly", as if something had ripped its way out. Indeed, the name Gator Bait came from a news story out of the Everglades, in which a python swallowed a gator far too large and the snake's belly burst open. This felt much the same, as Pesca Pod and Gator Bait could each exist just fine on its own. A short time later, I asked a professional photographer to take some studio photos. I enjoy watching people interact with my work, and David didn't disappoint. He strung some fishing line through Pesca Pod and hung it vertically. This simple change in perspective visually transformed the piece from a fish shape into a butterfly chrysalis. Many artists will admit that certain creations speak to them as they work, and I am no exception to that experience. Listen to the tree, for it will speak to you. Splint does not argue when you pay attention. A happy weaving will sing. In my humble opinion, baskets are a lot like people. Listen closely, pay attention, avoid arguments, and they will sing... It was a warm summer day when I first heard it. I was strolling through an art show in Marquette, MI, and an earthy, steady rhythm grew louder as I approached: whomp, whomp, whomp...whomp, whomp, whomp.

The sound's source was tucked behind a display booth, where a Native artist was methodically striking a fresh black ash log with a heavy mallet. I watched in awe as growth rings lifted one by one. He handed me a satiny ribbon of wood that could be tied into a knot without breaking or fraying. I had been weaving with rattan for several years and longed for a different medium. A sound had drawn me to black ash, and I was immediately hooked. A few weeks later, I followed Mike Sagataw into the wet woods. "Pull on your swampers and grab a saw," he said. "We're headed towards that stand of cedar out back." After choosing a suitable basket tree and sawing partway through its trunk, Mike removed the saw and produced a small deerskin pouch. A tobacco offering thanked Mother Earth. A prayer and honor song lifted skyward in a language I didn't speak, yet somehow understood. Mike had just introduced me to another beautiful sound: the Ojibway language, Aanishnaabek. Hauling the tree home was no easy task. We each hoisted a 6 ft log and picked our way through ankle-deep mud. Then the hard work began: the entire log had to be pounded with a 4-pound sledge hammer. As we worked, growth rings lifted in long strips, often 7 or 8 rings at a time. He showed me how to subdivide the thicker rings to make thinner splint, how to smooth the rough side with a sharp knife, and how to trim the splint into uniform widths for weaving. But he refused to teach me anything about weaving with ash. "Listen to the tree," he said. "It will tell you what it wants to become." |

AuthorMarcia Morse Mullins |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed